CAPTAIN KRONOS, HAMMER FILMS, MICHAEL CARRERAS....1974 AND ALL THAT!

At the end of the day, I have to shrug and surrender to my baser side and say that Michael Carreras probably needed to be kicked in the shin at least once. Possibly more than once, but at least once. Allow me to explain myself. Michael Carreras was the son of Hammer Studio founder James Carreras, and he used that relationship to finagle himself a more or less permanent fixture in the hierarchy of the studio, until eventually the reigns were passed to him entirely and the whole show collapsed. Now not everything with the name of Michael Carrereas on it was an embarrassing display of nepotism.

In fact, there is much about Michael’s involvement with his father’s studio that is of high merit. He served as producer for most of the studio’s best films. As a director, he was a mixed bag, but he did manage to deliver The Lost Continent, one of Hammer’s loopiest and most hilariously daft adventure films. And after directing a decidedly pedestrian follow-up to Hammer’s smash hit The Mummy, he redeemed himself somewhat by stepping in to finish the job of directing the superb Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb when original director Seth Holt passed away. No, there is much about Michael’s tenure at Hammer that is worth celebrating. It’s just that at some point in the 1970s, he lost his mind.

I think by now, we’ve covered the demise of Hammer Studio in the 1970s enough times that I don’t need to go into much detail here. You should know the drill by now. The Hammer formula, which had been so bold in the early 50s and throughout the 60s, failed to keep pace with changing social values and cinematic trends so that, by the end of the 1960s, their once fierce and rebellious content looked quaint and old-fashioned compared to what everyone else was doing. Studio head Michael Carreras was thus desperate to right a sinking ship and discover some way to keep the studio afloat. On top of that, however, was lumped the general collapse of the British film industry, meaning that Carreras suddenly went from trying to save a sinking ship to trying to save a sinking lifeboat tied to a sinking ship. It is not, obviously, an enviable position in which to have been. But it was not an unwinnable situation, as other studios would prove. The key was to adapt. But it was with the task of adapting that Carerras proved singularly untalented despite — and likely because of — all else he’d accomplished.

Horror films had changed dramatically, thanks in large part to the pioneering films of Hammer. With the release of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and The Omen, horror showed a marked move toward not just Satanic-themed films, but toward more cynical “evil triumphs” films. While major studios were finally deeming horror a genre worthy of their attention, low budget and independent film makers were turning out stuff like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, far more visceral and completely different than anything that had come before and certainly much more extreme than anything Hammer was willing or even able to produce with the BBFC looming over them. The focus of horror shifted significantly from England to the United States, and since the United States had always been a major market for Hammer’s product, they found it hard to compete with the home team. Things were no different in mainland Europe, where the Italian giallo thrillers were also pushing the envelope far beyond what British censors would allow Hammer to get away with.

The boys from Bray may have pushed the envelope in terms of sex and violence for ten years, but by the time “The End” appeared, good usually triumphed and the creature, either tragic or evil, was vanquished. But these new horror films were happy to let evil win. There was no way Hammer could compete with that, just as there was no way they could compete with a major Hollywood studio taking an interest in horror. Lower budget American horror film, largely produced by American International Pictures and their imitators, surpassed in sex and violence the Hammer product that had helped inspire them so many years before. AIP, in particular, seemed to understand that while there would always be big studio horror films aimed at adults, for horror to survive as a whole, a shift had to be made away from adults and toward teenagers. Teens, since the early days of AIP, had played a central role in the success of the studios films. Post World War II, there was a whole generation of young people who began earning money not to help the family survive, but so they could spend it on the stuff they wanted. Most films, however, were aimed either at adults or children. AIP stepped in and made movies for teenagers, and the results were solid gold.

Hammer, by contrast, had never really targeted teens as an audience. When, toward the end of the studio’s lifespan and desperate for some new revenue stream, Hammer finally tried to throw a bone to the younger generation, it was generally pretty feeble and had the feel of old men trying to write in the persona of a younger person about whom they knew next to nothing. Thus you get the goofball but not unappealing mixture of 60s mods and early 70s hippies that show up in Dracula AD 1972. But even disregarding the screwy attempts at seeming young, Hammer wasn’t speaking to the kids. Whenever AIP made a movie for teens, they were keen on making sure there were as few adults present as possible.

Those who were, were often ineffectual authority figures, crackpots, or oppressive parents against whom we rooted for the kids to rebel. In the end, it was the younger generation that saved the day, usually in some way that involved a surfing competition or young hot rodders zipping around a small southwestern town in their dune buggies. Hammer, by contrast, could never really divorce itself from authoritative paternal figures. So while Dracula AD 1972 may have been full of hip kids spewing misguided attempts at youth slang, it’s stolid old Peter Cushing who sweeps in to clean up the mess and save the day. And as photos have proven you can dress Peter Cushing up in a hip hop jacket and baseball cap, but there’s still the stuffiest stuffy old man suit in the word beneath it all.

So Michael Carreras was creating a no-win situation for himself. On the one hand, he wanted to find something new and invigorating for the studio to do. On the other hand, his ideas were terrible and all seemed to revolve around comedies about people tripping while going up the steps of a public bus. On the one hand, he said Hammer needed a new direction, something away from horror or more in line with what modern horror had become. On the other hand (Hammer had a lot of hands), at the end of the day, all he could think of was to do the same old, same old, but with more nudity. He wanted to do something different, then he complained when directors tried to do something different. In a word, Michael Carreras was lost.

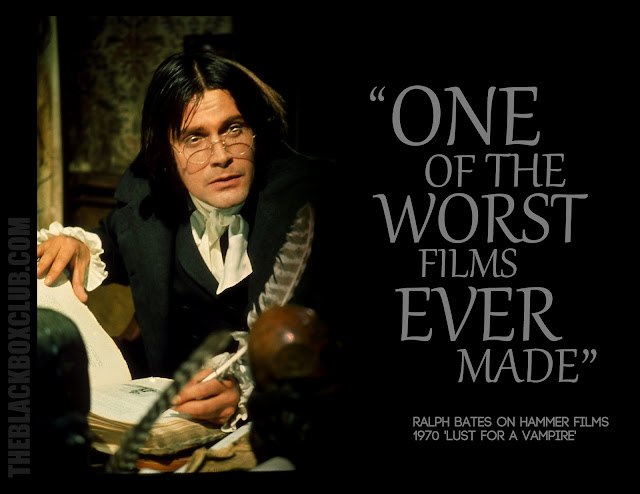

I don’t know what blinded him exactly other than having too many fires to deal with while being too stuck in his old ways, because the remedy he needed was right in front of him. With the tanks of both the Dracula and Frankenstein films very nearly empty, Hammer turned to three other stabs at vampire films in hopes that something might stick and give them a new franchise that would keep the studio hobbling along for at least another year. The most successful of these attempts was the Karnstein trilogy, three films based loosely on Carmilla and notable for being the point at which Hammer finally shrugged and started showing boobs (thanks largely to the involvement of AIP as a production partner). The trilogy produced two of Hammer’s very best horror films (Vampire Lovers and Twins of Evil) and one of their very worst (Lust for a Vampire). The second attempt was Vampire Circus, in which the studio attempted to put a twist on their vampire theme by looking toward the dreamier, more hallucinogenic horror films of continental Europe (specifically France and Italy). It’s a very good movie, but it was simply too weird for Hammer, and possibly too weird for most British and American audiences, or so thought Carreras.

The third attempt was a curious combination of the studio’s tried and true vampire formula mixed with a dash of the old swashbuckling “pirate movies without pirate ships” Hammer made in the early 60s, combined with something Hammer had never put in any of their previous horror films: a sense of humor. This was Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter, and it remains my very favorite Hammer film and one of my favorite films in general. A pity that Michael Carreras didn’t see things the way I did.

While Hammer in the 70s may have been flailing, that doesn’t mean they didn’t produce a lot of great movies. In fact, it was likely because the studio was in such dire straights that they were willing to try almost anything — or at least claim that they would try almost anything, sort of like how I’ll claim to eat anything at least once, until someone actually calls my bluff and tries to stuff a grub in my mouth. This meant that an influx of new talent emerged from the long shadows of Terence Fisher, Jimmy Sangster, and the rest of the extremely talented but rather aged old guard. Among the men employed by Hammer to try and freshen things up a big was Brian Clemens, best known at the time as one of the integral parts of the hugely popular British television series, The Avengers. In that way, perhaps, Hammer had hired one of the very men who was helping to destroy the studio.

The success of The Avengers was unparalleled, and while it may have started out initially as just a television show, by 1967, it was being shot in color and boasting production values that would rival many films. On top of that, the series had the perfect blend of old guard, represented by Patrick MacNee as John Steed with his bowler and suits, and new — as embodied first by Honor Blackman, but then taken to a whole new level by Diana Rigg as Emma Peel. The scripts hewed to a basic formula, but they were highlighted by smart dialog and witty banter between the two incredibly likable leads. And even Steed, despite looking every bit the British gentleman, had a streak of rebelliousness and irreverence that made him appealing to younger viewers.

Production company ITC was quick to follow the example set by The Avengers, and before anyone knew it, British television was full of action and adventure series that were in color, trotted the globe (or at least parts of England made up to look like the globe), and took far more risks than more expensive, slower to adapt movies. If you were a bright young writer or director looking to do something unusual, you were much better off working on one of the many ITC shows — first espionage and, in the 70s, bad-ass cop shows. I don’t have the data to claim that these high production value shows were the main reason the film industry was hurting, but they certainly made a dent.

When Clemens got the chance to direct a film for Hammer, he went for it (The Avengers having wrapped up by that time). The story he brought with him was very much of The Avengers mode, with a sassier female character than Hammer had ever had before, a script full of wit and dark humor, and perhaps most striking of all, a hero.

As Clemens described things, part of the problem he saw with Hammer’s Dracula films wasn’t so much that they were slaves to convention; it was that Dracula was the hero, or the anti-hero a the very least. Even though you knew he would die at the end, you still went to root for Dracula, because the people lined up as his nominal opponents were so incredibly forgettable and had been since the third film. Gone were the days when you had a hero as charismatic as Peter Cushing to cheer for. Dracula, Prince of Darkness had that gun-toting friar, but since him, who was there to go against Dracula? A seemingly endless parade of trembling clergymen and forgettable young blond guys named Paul. For lack of anything else, audiences began to side with Dracula — which is a testament to just how boring the heroes were, since Dracula usually had about five minutes of total screen time and spoke like three sentences.

Clemens wanted to change that, to give audiences a vampire movie where the vampires were the bad guys again and where there was a proper hero for whom people could root. For this character, Clemens drew largely upon the swashbuckling heroes of the past, and so was born Kronos, a vampire hunter — possibly immortal himself — possessed of a mysterious history, a knowing smirk, and a professor friend who, while older and wiser, is far away from the “knows what’s best for you” paternalism of Cushing’s Van Helsing. There was something of the counter-culture about both Kronos and his adviser, Professor Hieronymos Grost. Grost’s knowledge, after all, is of an arcane and in some cases profane nature, and if Kronos was a captain in some army, it must have been the same army as Oddball from Kelly’s Heroes. They seem both to have eschewed the traditional authoritative hierarchy of academia and the military in favor of just cruising around on their own, doing their own thing. This lack of respect for authority extends as well to other circles of the upper class: religious leaders, community leaders, the rich and powerful — Grost and Kronos seem happiest away from these types, camping out in a barn with a hot servant girl they rescued from being executed.

Clemens further twists the traditional vampire movie formula by proposing a world in which there are as many different types of vampires as there are types of dog, each with its own unique characteristics, powers, and weaknesses. In another nod to the film’s appeal to youth over tradition, the vampires against which Kronos finds himself pitted do not drain their victims of blood, but of youth. Likewise, the way in which you kill one vampire might not work on another (a conundrum which results in the film’s most devilishly funny scene, in which Kronos and Grost cycle through the entire array of ways they know to kill vampires, until they finally find one that works). In a way, this representation of vampires is a natural outgrowth of the theories on vampirism presented by Cushing’s Van Helsing way back in Horror of Dracula and Brides of Dracula. Back then, before Dracula became a Satanic prince of evil and conjured demon, Van Helsing framed the vampire in purely scientific terms. They were a part of our natural world, albeit a part that did not conform to the behavior one expected of creatures who looked like humans. Vampirism was a communicable disease rather than some Satanic curse or the result of corny rituals. Captain Kronos seems to pick this thread up and expand it, creating an entirely new species within which there are many natural variations.

Although I can’t say for certain if it was intended as such, it also works as a pointed satirical jab at the vast proliferation of ways in which you could kill and resurrect Dracula that were created out of necessity to facilitate yet another sequel. By the end of things, vampires were being killed by stakes, crucifixes, icy creeks, hawthorn bushes, lightning, windmills…who could keep track? So in the world of Kronos, you never quite know what will kill a vampire. Tradition does not work. Nor do you know exactly what effect its bite will have on you. As I said, I don’t think it’s an accident that the vampires in this film prey upon the young and drain them of their youth. In the climate of the 1970s, it’s the established powerbase exploiting the young, crushing them under the weight of an increasingly creaky traditional society, draining them of their vitality even as the vampires feed upon it for their own energy.

Although other Hammer films had taken swipes at certain established authority figures — witness, for example, the corrupt men in Taste the Blood of Dracula, or the ineffectual and cowardly priest in Dracula Has Risen from the Grave — this one the first time since perhaps The Pirates of Blood River that the studio gave audiences an uppity, charismatic, young firebrand willing to buck the system. Hell, Kronos even smokes the occasional 18th century doobie! At last, there was a Hammer movie and a Hammer hero that young people could actually get behind and perhaps even relate to. Someone who was more like one of them rather than like a parent, standing around waiting to disapprove and tell the whippersnappers how to properly do things.

Clemens’ movie is different right out of the gate. Just as he was a Hammer outsider, working with a cast comprised largely of newcomers and outsiders, he also went outside the norm in searching for a composer and a style of music to accompany the film. He tapped Laurie Johnson, who had worked previously on The Avengers, among many other projects for film and television, to give the movie a theme that stood in stark contrast to the masterful but overly familiar “Hammer horror sound” created primarily by James Bernard. Bernard’s scores were heavy, bombastic, and thunderous. Johnson’s theme for Captain Kronos, however, is fast moving and much lighter. It’s a combination of a theme from a swashbuckling film with the theme from a horror film, very much a reflection of Grost and Kronos themselves. Where as Bernard’s themes stalk and stomp, Johnson’s theme here gallops and parries.

Far away from the three piece Harris tweed and pocket watch look of most vampire hunters, Kronos is a mixture of pirate and soldier in appearance, with bushy blond hair and a rapier. Grost, by contrast, is a bespectacled, goateed hunchback, though he’s far from grotesque. They are two halves of a whole — the muscle and charm in Kronos, the brains and wit in Grost. For the lead role, they cast German actor Horst Jansen, and he certainly looks the part. Tall, confident, sexy, and swaggering. Even though they’re in the same profession, there’s very little of Van Helsing about the man. Kronos looks less likely to have been spending his days steeped in researching of arcane folklore and more likely to be lying on the beach, a tan young woman on one side and his surfboard on the other. What he learns, he learns through experience or via the wise counsel of Grost. Unfortunately, Jasen’s limited English results in something of a wooden performance, though for me it never really mars the film, as he’s carried by John Cater as Grost, a more than capable actor who is so good and so charming in his role that you don’t even notice most of the time that he’s a hunchback — though on occasion I mistook him for Lenin. Luckily, Grost is way more fun to be around and is a lot less likely than Lenin to have you executed for some trifle.

The duo are en route to a town that has been plagued by a series of mysterious attacks on young people who are found after the attack drained of decades and aged to the point of death. Kronos stops to liberate a beautiful young gypsy woman (Caroline Munro, recently featured in the studio’s Dracula AD 1972), who has been condemned for something Kronos and Grost find idiotic by men whom Grost and Kronos find equally idiotic. Thankful for her liberation, she swears servitude to the two adventurers, and while neither man seems overly keen on having a slave, neither does any man seem to find much fault in being accompanied everywhere by Caroline Munro in a peasant blouse with a plunging neckline. And later, when she offers herself to Kronos, he does what any man would do, and does not hesitate. A hero who smokes weed and enjoys sex? Where do they come up with this crazy stuff?

Kronos and Grost have been summoned by their old friend, Dr. Marcus (John Carson), who resides in the beleaguered town and knows that his two friends specialize these days in dealing with such peculiarities. Kronos, in particular, has it in for vampires, as both his mother and sister were killed by one. And while the process of draining a victim of youth rather than blood is slightly beyond the pale of a traditional vampire, Grost recognizes that tradition only accounts for a small percentage of what people know or don’t know about vampires. Soon the gang is on the case, sword fighting and riddle solving their way to the culprit behind the strange murders.

The overriding philosophy behind this movie seems to be that Hammer horror hadn’t been scary for a long time, and it wasn’t going to be scary anymore. So why not make one that was exciting? And that’s exactly what Clemens did. Captain Kronos moves fast and boasts plenty of action. Jansen may be a bit stiff with his lines, but he looks good in a fight scene, and he gets plenty of them. Clemens’ experience with television meant he knew a lot about taking a meager budget and limited sets and making them seem far more lavish and expansive than they actually were. The result is one of the best looking films Hammer made during the period. Clemens made a lot of use of outdoor locations, which when coupled with the tone of the story makes Captain Kronos feel much more epic than the largely soundstage-bound Dracula films. He pulls off an epic feel, or at least a mini-epic feel, in much the same way John Gilling did when directing the “pirate movies without pirate ships” for Hammer a decade earlier.

The supporting cast is top notch. Cater and Carson are old hands, and they deliver the goods as all solid British pros know how to do. Caroline Munro was on the fast track to becoming an icon, and while her role here as the gypsy Clara isn’t as iconic as, say, the space bikini in Star Crash, it’s still a role that is both energetic and sexy. There’s something about the woman that simply transcends everything. They really don’t make them like her anymore, do they? While her role here may not be as meaty as the lads’, it’s still one of the best developed female roles Hammer ever had.

If Hammer was looking for something new, a franchise upon which to hang the fortunes of the studio, they had found it. Captain Kronos is just that good. Unfortunately, Carreras was waiting around like one the youth sucking vampires from the movie. In Carreras’ own words, he visited the set one day to see how things were going and was aghast at what he saw. Clemens and his crew, Carreras felt, were not handling the material with the proper gravitas. Instead, they were making light of things, having a bit of fun, injecting a wicked sense of humor into a previously humorless genre. Clemens did not, according to Carreras, get it. He didn’t understand the proper tone of a Hammer horror film the way the old guys did. In other words, Carreras hired Clemens to give him something fresh and inventive, and then he got pissed off when Clemens gave him just that.

As much as Carrereas’ attitude irritates me, and as much as it embodies everything that was wrong with Hammer’s attempts to adapt to the changing times, it’s hard to lie the failure of Captain Kronos to become a franchise player entirely at the feet of the floundering studio head. Audiences had already lost interest in Hammer. The studio was done for. It would have taken a miracle to save it, and while Captain Kronos is cracking good entertainment, it’s not a miracle. Along with audiences, distributors had lost interest in Hammer as well. One of the things that had kept Hammer afloat was their fruitful partnership with American distributors. But those days were over, because Americans were doing Hammer better than Hammer, and under a ratings code that was far more liberal than what the British Board of Film Censors wanted to be. As such, it took almost two years for Captain Kronos to get released, and by that time, the game was over. Hammer had used up the last of its audience good will, and viewers didn’t embrace the film despite the fact that the few reviews it received were generally positive.

It’s a shame, isn’t it? Clemens vision for Captain Kronos as a film series was pretty cool, with Kronos appearing throughout different periods across the centuries, carrying on his battle with the undead and revealing that there was a much longer history behind the man than has hinted at in the first movie. When it was evident that there was no way Hammer was going to make it, and thus there would be no second or third Kronos film, talk shifted to production of a television series. Nothing ever came of that, either, and with the exception of a few appearances in a Hammer comic book, Kronos faded from existence until more recently, when it was rediscovered and people started thinking, “Holy crap, this movie is great!” Now it enjoys a lace in many people’s top five Hammer films, making it sort of the On Her Majesty’s Secret Service of the vampire movie world.

Which is doubly fitting since that once-maligned entry into the James Bond Franchise was saddled with a stiff leading man and found itself situated in a time when the series was trying to recover from the loss of the iconic Sean Connery (and the rise of social discontent). Like Horst Jansen, George Lazenby was top notch in the action scenes though, and just as Horst had a cool sidekick and a gorgeous gal, Lazenby was carried by a cool ally and the best Bond girl of all time, The Avengers‘ Diana Rigg.

What’s more, it’s a shame Hammer couldn’t pull out of the collapse. Maybe if Captain Kronos had been a bigger box office hit, and maybe if Michael Carreras had shown a little faith in the film, then Hammer could have made good on that tantalizing poster art for movies they intended to make but never had a chance to get to. Don’t tell me you don’t want to see Zeppelin vs. Pterodactyls or didn’t hope Hammer wold make good on all that cheesecake nudie sci-fi artwork on the poster for When the Earth Cracked Open. Sure, they probably would have ended up less like the insanely awesome movies in my mind and more like one of those “lost world” films from Amicus Studio, but you know what? I loved those “lost world” movies from Amicus, so I would have been pretty psyched to watch something in which cheap looking little models of biplanes and blimps go head to head with wobbly pterodactyls on strings.

But those are exercises in what might have been, and while fun, the fact is there was never a Zeppelin vs. Pterodactyls or a Captain Kronos series. No Kronos fighting vampires down through the ages. What we have instead is a single Captain Kronos that happens to be an incredibly good film. It’s really everything I want from my entertainment. Fast paced, witty, irreverent but also a very good entry into the genre with which it is toying. I don’t think I’d argue that there aren’t flaws for people to find in the film, but if they are there, I’m not really all that concerned with finding them. Had this been the last film Hammer made, it would have been a perfect swan song. Our heroes, riding off beyond the horizon to face down evil. Would we ever see them again? Who knows?

Instead, Hammer ended up with a few more death twitches and even more misguided attempts at finding a new market. Among these were an ill-advised attempt to replace the lost American market with the exploding Hong Kong market by partnering with the Shaw Brothers studios to produce two films: the plodding action caper Shatter starring Stuart Whitman and Shaw Bros superstar Ti Lung, and the entertaining but ridiculous Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires, starring Peter Cushing and Shaw Bros’ star David Chiang. Both were attempts to cash in on the rising kungfu craze, and both failed. In the case of Shatter, it was hard to convince audiences that they should stop watching Bruce Lee and Five Fingers of Death and concentrate instead on a movie in which Stuart Whitman wanders around. It was like trying to convince Hong Kong audiences in the 80s to stop watching Jackie Chan and embrace Steven Seagal. Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires featured Cushing as Van Helsing, traipsing around China, but it never really feels like an actual Dracula film — possibly because venerated horror film icon Christopher Lee finally made good on his boast and refused to appear in the picture, even though Dracula transforms into a Chinese guy in the very beginning of the picture. Instead, it feels like a Shaw Brothers kungfu film into which Peter Cushing wandered by accident. It’s pretty fun, in my opinion, but there’s no mystery as to why it wasn’t the film that salvaged Hammer’s reputation.

The end to Hammer horror finally came in 1976, in the form of To the Devil…A Daughter, Hammer’s painfully horrible attempt to cash in on the devil worship movie craze that seized us in the 70s. Too bad the film was dreadful — in my opinion the only completely unwatchable horror film Hammer ever made. It’s too bad Kronos wasn’t around to put that one down before it sucked so much life out of us. But so it goes, and whatever might have happened doesn’t change how much I enjoy Captain Kronos.

I suppose I’m happy to be watching these films after the fact. I’ve never felt that Hammer films were stodgy or old-fashioned, or that they had dated poorly, but that’s probably because I’m watching them from a vantage point removed from the original cycle. If I’d been able to write reviews in the late 60s or early 70s, I probably would have been complaining about the lack of originality, so on and so forth. I love Hammer films. I love the old ones. I love the ones from the 70s. Heck, I even enjoy failures like Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb and Lust for a Vampire. In nearly two decades of film production, Hammer made one solitary horror film I can say I hate. That, my friends, is not a bad record, and I guess if I’d been in the shoes of Michael Carreras, I would have been as confused as he was.

But then, I’m just a writer and a fan, not the head of a studio. I expect more from him than I would from myself, what with how it was his job and all. I appreciate everything the pioneers did — Jimmy Sangster, Terence Fisher, James Bernard, John Gilling — my God but they made some incredible films. And I love the years in which Hammer was trying to figure the strange new world out. I love Twins of Evil, Vampire Circus, Taste the Blood of Dracula, and I don’t hate Lust for a Vampire or even Horror of Frankenstein. So flailing or not, misguided or not, with the final credits having rolled on Hammer (I’ll believe the persistent “we’re back!” press releases and announced productions when I see at least one final product), all I can do is raise a glass of brandy to them (I prefer scotch, but what would Peter Cushing say?) and say, with complete earnestness, “Thank you.”

Review:

Here

Images:

Marcus Brooks

Review:

Here

Images:

Marcus Brooks