Monday, 16 December 2013

JOAN FONTAINE 1917 2013

Labels:

alfred hitchcock,

hammer films,

joan fontaine,

letter from an unknown.woman.,

rebecca,

suspicion,

the witches

Sunday, 15 December 2013

LINDA HAYDEN: BLOOD ON SATAN'S CLAW AKA SATAN'S SKIN : RARE PHOTOGRAPH

Labels:

: anthony ainley,

blood on satans claw,

brit horror film.,

dr who,

linda hayden,

patrick wymark,

publicity photograph,

the devils skin,

tony tenser

Sunday, 8 December 2013

THE HAUNTED WORLD OF MARIO BAVA: BLACKBOXCLUB TALKS TO AUTHOR TROY HOWARTH

His style is hard to put into

words. He was, first and foremost, a

very visual artist. He conveyed volumes

of information through imagery. Barbara

Steele said he would have made a terrific silent filmmaker and she’s quite

right. But there’s a common

misconception that people who are aggressively visual are awkward when it comes

to story and so forth. I think he was a

tremendous story teller, truthfully. He

was able to convey things with great economy and his films were, I think, quite

lucid and easy to follow. I guess you

could describe his style – at least up until the early 70s – as Baroque. After that, he embraced a more realistic

aesthetic… but the point of view remained the same. As to category… I guess it’s fair to

call him a genre director – but not exclusively horror. He spread his talents over different

genres. He made westerns, sci-fi,

comedies… he did a little bit of everything – and he did it mostly very well.

What is his defining film?

It’s not my favorite, but there’s no

escaping the impact that Black Sunday

had on his career. It was his first “official”

film as a director. What I mean by that

is, he had completed other films without credit, even a couple basically from

the get-go, but this was the first time he was a credited director. He was very reluctant to make the leap to

directing, thinking he didn’t have the talent for it.

How did he come into film making?

He entered in the 30s, and was

initially responsible for designing the Italian titles sequences of various

Hollywood imports. He liked doing this

job but needed to earn more money to support his wife and children, so he

gradually made the transition to cinematography. He learned a great many tricks from his

father – Eugenio Bava. Eugenio designed

FX and did camerawork on Italian films of the silent era. Mario developed a passion for trick shots

early on and would become much sought-after in this capacity.

His background?

Mario had wanted to be a painter, but

realized it was a very unpredictable field – and again, lacked faith in his

abilities. He was a very self-doubting

person in many respects. He knew he was

a good technician, but as a director he always minimized his talents. Indeed, it can be said that he sabotaged

himself by basically denigrating his own work on those rare occasions when he

granted interviews. I think that he liked

being anonymous and as such avoided any attempts that writers would make

towards putting him forward as a “serious” artist. I mean seriously, how many people would call

their work “bullshit” in interviews?

Many should, perhaps, but would never dare!

Who did he work with from other fields and film types?

He and Roberto Rossellini began

together – Bava shot Rossellini’s first documentary film. He also photographed films for G.W. Pabst,

Jacques Tourneur and Raoul Walsh, among others.

They were all impressed with him.

Walsh essentially said that if the industry had more people like Bava,

it would be a lot better off.

What were his successes and failures?

Depends on how you quality success and

failure. Most of Bava’s films failed

commercially in Italy, and much of his work failed to secure much distribution in

the 70s. He made two very personal “pet

projects” back to back in the 70s – Lisa and

the Devil and Rabid Dogs. They were very different films. Lisa

was a very arty project, while Rabid Dogs

was an attempt at a gritty thriller designed to reestablish himself as a

presence in the Italian film scene. They

both ended up being major disappointments.

Lisa couldn’t secure

distribution, so it was later reedited with some new footage as House of Exorcism. Bava reluctantly shot

some of the new material before leaving to work on Rabid Dogs. Rabid Dogs fell into legal turmoil when

the producer died and the money dried up; it would sit on the shelf until long

after Bava’s death. These two experiences

were especially dispiriting for him. In

the international scene, he scored major successes with Black Sunday and Black

Sabbath. Diabolik was a big film for him – a Dino De Laurentiis production

with stars and a generous budget… but he hated being micromanaged and resisted further

offers to work with De Laurentiis again.

He preferred making small films with low budgets and total creative

freedom. But even on Diabolik, he managed to retain control –

he brought the film in very much under budget.

Producers loved him and trusted him.

Was he open to criticism?

He was certainly open to collaboration

and would welcome ideas and contributions… his films were not well reviewed as

a rule, and he would laugh this off – but those who knew him said that it did

bother him. He put a lot of heart and

hard work into his films. But he wasn’t

seen as “intellectual” by the press, so his work was dismissed as trash. He was very devoted to his father but,

reading between the lines of various comments, it seems that Eugenio was rather

hard on him. I think this stayed with him.

Who influenced him and who did he influence?

He wasn’t overly influenced by many

filmmakers that I can see. I see a bit

of Cocteau here and there… but in general, his influences were more literary,

believe it or not. He was a voracious

reader and he adored Russian literature, especially of a fantastic nature. He certainly loved Charlie Chaplin,

however. Who did he influence? Quite a few, ranging from Dario Argento and

Joe Dante to Martin Scorsese and William Friedkin. Scorsese, Friedkin and Quentin Tarantino have

all singled him out for special praise.

You can see elements of Bava in Scorsese’s Shutter Island and Cape Fear,

for example, while Dante’s recent film The

Hole contained an explicit homage.

Fellini also borrowed from Bava – the image of the ghostly girl in Kill Baby Kill! inspired his short film Toby Dammit, which was part of the Edgar

Allan Poe anthology, Spirits of the Dead. The critics may not have taken him seriously,

but people like Fellini and Visconti certainly did.

Who did he prefer to work with, actors, crews?

He wasn’t crazy about actors as a general rule, though he became friendly with some of them. He became a bit embittered towards Barbara Steele when she passed on The Whip and the Body – he thought she was becoming snooty about genre films as she had just done 8 ½ for Fellini, but then she did Castle of Blood for Antonio Margheriti. I think he saw it as a bit of an affront and would make some uncharacteristically catty comments about her in later interviews. That wasn’t like him in general, so I think that irked him and he misunderstood what had happened. He liked Cameron Mitchell immensely. He adored Boris Karloff. He must have liked Christopher Lee, as he used him twice – and was set to use him again on a project that fell through. He loved Daria Nicolodi. He used a couple of character actors numerous times: Gustavo De Nardo and Luciano Pigozzi. But he was most comfortable with his crew. His son Lamberto assisted him for many years. He used his father on his films up until his death in 1966. He was very loyal to his crew.

Tell me about the music in his work..

Not much has been written about his use of sound and music, which is a pity. He used certain composers a lot – Roberto Nicolosi and Carlo Rustichelli come to mind. I think he liked working with them and responded to what they brought to it. Many of his films were rescored when American International acquired the English language rights. You only have to hear the soundtracks they did without his input to realize how carefully he used music – and more importantly, silence! – in his films. A great many of his films have marvelous soundtracks. He only did one film with Ennio Morricone, sadly, but it was a great collaboration: Diabolik. I can’t say for sure, but I think he may have been the first director to have used a rock song in a horror or thriller context. I’m thinking of the use of “Furore” by Adriano Celentano over the titles of The Girl Who Knew Too Much. Dario Argento would get a lot of credit for this later, on Deep Red and Suspiria, but Bava beat him to the punch. He would also use a rock song at the end of Five Dolls for an August Moon. But the piece of music he was most obsessive about in a certain film was “Concerto d’Aranjuez” which he played on the set of Lisa and the Devil – the Paul Mauriat arrangement is used extensively in the finished film, and it suits the melancholy mood beautifully.

Your top three Bava films?

Lisa and the Devil, The Whip and the Body and Blood and Black Lace.

Was there anything he wanted to do but did get around to, unfulfilled projects?

He wanted to do a Lovecraft adaptation

but worried that it would be impossible to realize his peculiar brand of horror

on screen. I think he could have done it, though. Hercules

in the Haunted World, Planet of the

Vampires, Kill Baby Kill! and Lisa and the Devil all have elements

that can be called Lovecraftian. He also

wanted to adapt the same story that inspired Elio Petri’s A Quiet Place in the Country; he liked the film that Petri made,

however, and wasn’t about to try and compete with it. He was busy developing projects to the day he

died… you can read about these in-depth in the book when it’s released.

Give me the title of THE one to see, if I wanted to watch a good example of Bava..

If I wanted to show somebody a Bava film that could potentially ease them into his universe, I’d say Black Sabbath – or rather, the Italian version, The Three Faces of Fear. American International ruined it when they released it in English – they were able to get Karloff to dub it, of course, but they changed the editing and the music and greatly diminished the impact. The Italian edit is a great “primer” to all things Bava, however.

What is the 'ALIEN' (1979) Bava connection?

This is a point of contention among the creators of the film. If you watch Alien and Bava’s Planet of the Vampires, you will see there are some similarities – not enough to make the Ridley Scott film an imitation, by any means, but enough to show an influence. I frankly believe that the screenwriter Dan O’Bannon – a genre nut who had worked with John Carpenter on Dark Star and would go on to direct the marvelous Return of the Living Dead – borrowed a few ideas from the Bava film – but he never copped to it. Anyway, the proof’s in the pudding, as they say….

What do think he would have hoped his legacy to cinema could have been?

I think that although he acted like he didn’t take himself seriously, he would be pleased to know that his work continues to inspire filmmakers. Above anything else, I think he would love to have been remembered for his technical prowess – his ability to conjure up something out of nothing, like a magician.

Tells us about the twist in how his life ended

It’s

sad – he was preparing to make a film, and he had to get a physical for

insurance purposes. Tim Lucas goes into

all of this in his book: the exam showed no problems… but he would die of a

heart attack just a few days later. He

was a workaholic and he smoked like a chimney… he aged very rapidly in his last

years, so he looked much older than his years, but he was only 65 when he

passed away.

And finally, the book why reissue?

Ooooh, this is convoluted. Pull up a seat and stay a while. Ha! I undertook the book in 1996 on a whim. I never would have thought I could write a book. I intended to write a magazine article. I couldn’t figure out why there were books on Argento and Fulci, but nothing on Bava. So I decided to write an article… then it developed into a monograph. I had no idea that there was another book on Bava in the offing – if I had known, I probably never would have followed through with it. It was a professor at college who gave me the encouragement to follow it through and get it published. I submitted chapters to FAB and McFarland, and they both were interested; I went with FAB because of the production value they could give it. It was a flawed book. I was very young when I wrote it and I like to think I’ve improved since then, so I was keen to revise it at some point – but FAB couldn’t commit to it due to other projects and their rights lapsed, so I shopped it around. I wasn’t getting anywhere, but then I tried Midnight Marquee and Gary was very enthusiastic. He and I were on the same page: we wanted to make it a better book than before and add in as much new material as possible.

The key thing to understand is this is not a reprint: it’s literally a new book. It’s updated, revised and expanded. It’s been a dream getting to go back and make it much better. One of the things I was happy to do was jettison the majority of the plot synopses. They were a necessary evil when I did the first edition – FAB was insistent that they be lengthy as the films were hard to see at that time. Now most of them are available, so we can get away with not going into that kind of detail… thank god! I hate plot synopses. I never read them and I hate writing them. In my reviews, for example, I put in a basic plot intro… and then an ellipsis… If you’ve seen the film, you don’t need a recap; if you haven’t, chances are, you don’t want to read too much of the plot ahead of time. Anyway, I was able to revise opinions that have since changed, tighten the prose and correct errors I made in good faith so many years ago. I’m frankly very happy with it now, and I never say that of my writing.

Finally, finally . . Four words that sum up bava, his life and work?

Style… humility… imagination… humor.

Labels:

barbara steels,

black sabbath,

black sunday,

cape fearwhip and the body,

diabolik,

eugenio bava,

giallo,

hercules.,

jacques tourneur,

mario bava. bava,

radib dogs,

troy howarth

Saturday, 23 November 2013

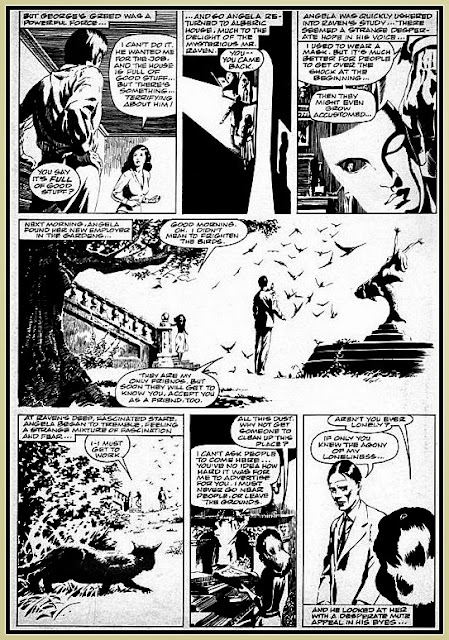

THE MONSTER CLUB: COMIC STRIP PART TWO

Labels:

amicus,

anthology film,

british horror,

comic strip,

comic strip.,

dez skinn,

donald pleasence,

elstree studios,

john bolton,

milton subotsky,

roy ward baker,

the monster club,

vincent price

Friday, 22 November 2013

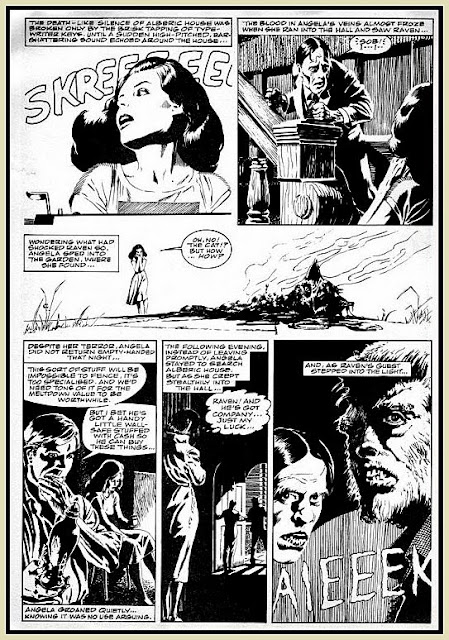

'THE MONSTER CLUB' COMIC STRIP STARRING VINCENT PRICE: PART ONE

Labels:

amicus films,

british horrro films,

chips,

comic strip,

deviant art,

elstree studios.,

itc,

john boulton,

john carradine,

milton subotsky,

monster club,

r chetwyn hayes,

shadmock,

vampires. ghoul,

vincent price

Monday, 4 November 2013

BREAKOUT THE COMICS: CUSHING AND LEE DO A LITTLE LIGHT READING

Wednesday, 16 October 2013

HAMMER FILMS PRESENTATION CARDS: DRACULA PRINCE OF DARKNESS

Labels:

Andrew Keir,

barbara shelley,

bram stoker,

bray studios,

count dracula,

dracula prince of darkness,

hammer horror,

vampire

Thursday, 3 October 2013

'MASTER BUILDER' THE HAMMER HOUSE HINDS THAT HINDS BUILT

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.”

Hinds was born in Middlesex, England, on September 19th, 1922. After

a stint in the Royal Air Force, he accepted an invitation from his

father, Will Hammer, to come and join the ranks at Exclusive Films. In 1948, he produced his first picture, a modest potboiler named Who Killed Van Loon?. Hinds

displayed an ability to bring his films in on time and on budget and

also showed a genuine concern for quality, which was something of a rare

quality for men in his position in the lower echelons of British film

production. In 1954, Hinds produced The Quatermass

Xperiment – in essence the first of Hammer (as the studio had by then

been rechristened) Films’ major commercial successes. A

tight, well-paced adaptation of a hit TV serial by Nigel Kneale, the

film disappointed its original writer, but proved to be a hit with

audiences. The film’s success prompted Hinds to push his

friends and coworkers at the studio to develop an idea for a follow-up

in a similar style. Production manager Jimmy Sangster won

the friendly competition by suggesting a story of radioactive mud which

has undesirable effects on those who come into contact with it, and

Sangster was then catapulted into a new career as a writer; Sangster

always remembered Hinds for having the faith in him to allow him to

write his first screenplay. The success of these early

black and white sci-fi/horror hybrids eventually lead Hammer, and

Anthony Hinds, into a new direction…

American writer/producer Milton Subotsky

approached Hinds with the idea of remaking James Whale’s Frankenstein

(1931), but Hinds wasn’t exactly wild about the idea. After

considering his options, however, Hinds decided that a brand new

approach to the Mary Shelley novel might prove rewarding – and he

proceeded to assemble an ace team of artisans and technicians to make

the picture. It was Hinds who also decided to push for

filming in color – a costly addition, in a sense, but one which the

producer wisely realized would pay off in dividends. The end result, The Curse of Frankenstein, would prove to be a watershed “event” in the evolution of the horror genre. With

its deceptively rich production

values and then-scandalous dashes of blood and gore, the film would go

on to become a box office triumph, revitalizing the popularity of Gothic

horror films at the box office and putting Hammer on the map as a major

player in the UK film production scene. Hinds decided to

reassemble the same team – director Terence Fisher, screenwriter Jimmy

Sangster, cinematographer Jack Asher, production designer Bernard

Robinson, composer James Bernard, and stars Peter Cushing and

Christopher Lee – for Dracula (1958), and the resulting film was met

with critical consternation and tremendous box office numbers. From this point on, Hammer was, as the saying goes, a force to be reckoned with.

Quite apart from being savvy enough to assemble the people who made these films so special, Hinds was also a rare producer who had genuine passion for film. He took pride in his work, and expected others to do the same. Hinds was by all accounts a humble, laid back individual – not exactly the kind of cigar chomping “mover and groover” one normally associates with producers. His thoughtful disposition prompted him to push his collaborators to take their work seriously. He knew the value of a pound, and saw to it that the films he produced were executed with a glossy veneer which hid their humble origins. It was an attitude that he did his best to implement on every picture he ever produced.

In time, Hinds branched out yet again, this time becoming a screenwriter. The

story goes that Hammer’s planned historical epic, The Rape of Sabena,

fell afoul of the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC), thus leaving

Hinds in a bit of a predicament. He had already authorized

Bernard Robinson to build some imposing “Spanish” sets, and now that

this particular property was dead in the water, he had to find a way to

utilize these sets. Hinds turned his attention to Guy

Endore’s novel The Werewolf of Paris – realizing that Hammer had yet to

make their own werewolf film, he decided to change the setting from

Paris to Spain, thus enabling the studio to make use of these

troublesome sets. Looking to save a

buck, Hinds elected to write the script himself – and he found that he

preferred the process of creating scenarios to dealing with the

bureaucratic nightmares associated with producing. Hinds

would continue to produce throughout the better part of the 1960s, but

when he found himself working “under” American producer Joan Harrison on

Hammer’s ill-fated venture into anthology television, Journey into the

Unknown, he decided to call it a day. Hinds would later

recall working with Harrison (or as often was the case, being at

loggerheads with her) on this problematic production to be a dispiriting

affair which he was in no great hurry to relive. And thus

it came to be that producer/writer Anthony Hinds became “plain old”

writer Anthony Hinds… or John Elder, as the self-effacing scribe decided

that having his

name plastered all over the credits might look a bit conceited. As

a writer, Hinds’ credits include Kiss of the Vampire (1962), Phantom of

the Opera (1962), The Reptile (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman

(1966), Taste the Blood of Dracula (1969), and Frankenstein and the

Monster from Hell (1972). He eventually left Hammer for a time, going to work for rival company Tyburn Productions. For them, he scripted The Ghoul and Legend of the Werewolf in 1974. His

final credits would include an episode of Hammer House of Horror,

titled Visitor from the Grave, and a “story by” credit on Tyburn’s made

for TV Sherlock Holmes adventure, The Masks of Death (1984), starring

Peter Cushing and John Mills.

Hinds went into retirement in the 80s, granting the occasional interview, but basically content to enjoy his “golden years” on his own terms. A quiet, humble and unpretentious individual, he reacted with genuine surprise (and pride) when his many classic Hammer productions were dredged up and celebrated as classics of their kind. True to form, Hinds never seemed to take himself too seriously – but his passion for the work itself was obvious. With his passing on September 30th (a mere 11 days after his birthday), the key architect of Hammer horror passed to the great beyond. Indeed, of the key creative personnel who created this world that we fans know and revere so much, only one remains standing: Christopher Lee, himself a mere four months Hinds’ senior. Hinds’ passing may not signal the end of an era, but it does put one in a reflective mood as we look back and celebrate the many wonderful achievements of one of the British film industry’s unsung treasures.

Troy Howarth

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Labels:

anthony hinds,

box office,

bray studios,

dracula.,

gothic,

hammer film productions,

journey into the unknown,

quatermass,

retro cinema,

watershed,

will hammer

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)