Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.”

Hinds was born in Middlesex, England, on September 19th, 1922. After

a stint in the Royal Air Force, he accepted an invitation from his

father, Will Hammer, to come and join the ranks at Exclusive Films. In 1948, he produced his first picture, a modest potboiler named Who Killed Van Loon?. Hinds

displayed an ability to bring his films in on time and on budget and

also showed a genuine concern for quality, which was something of a rare

quality for men in his position in the lower echelons of British film

production. In 1954, Hinds produced The Quatermass

Xperiment – in essence the first of Hammer (as the studio had by then

been rechristened) Films’ major commercial successes. A

tight, well-paced adaptation of a hit TV serial by Nigel Kneale, the

film disappointed its original writer, but proved to be a hit with

audiences. The film’s success prompted Hinds to push his

friends and coworkers at the studio to develop an idea for a follow-up

in a similar style. Production manager Jimmy Sangster won

the friendly competition by suggesting a story of radioactive mud which

has undesirable effects on those who come into contact with it, and

Sangster was then catapulted into a new career as a writer; Sangster

always remembered Hinds for having the faith in him to allow him to

write his first screenplay. The success of these early

black and white sci-fi/horror hybrids eventually lead Hammer, and

Anthony Hinds, into a new direction…

American writer/producer Milton Subotsky

approached Hinds with the idea of remaking James Whale’s Frankenstein

(1931), but Hinds wasn’t exactly wild about the idea. After

considering his options, however, Hinds decided that a brand new

approach to the Mary Shelley novel might prove rewarding – and he

proceeded to assemble an ace team of artisans and technicians to make

the picture. It was Hinds who also decided to push for

filming in color – a costly addition, in a sense, but one which the

producer wisely realized would pay off in dividends. The end result, The Curse of Frankenstein, would prove to be a watershed “event” in the evolution of the horror genre. With

its deceptively rich production

values and then-scandalous dashes of blood and gore, the film would go

on to become a box office triumph, revitalizing the popularity of Gothic

horror films at the box office and putting Hammer on the map as a major

player in the UK film production scene. Hinds decided to

reassemble the same team – director Terence Fisher, screenwriter Jimmy

Sangster, cinematographer Jack Asher, production designer Bernard

Robinson, composer James Bernard, and stars Peter Cushing and

Christopher Lee – for Dracula (1958), and the resulting film was met

with critical consternation and tremendous box office numbers. From this point on, Hammer was, as the saying goes, a force to be reckoned with.

Quite apart from being savvy enough to assemble the people who made these films so special, Hinds was also a rare producer who had genuine passion for film. He took pride in his work, and expected others to do the same. Hinds was by all accounts a humble, laid back individual – not exactly the kind of cigar chomping “mover and groover” one normally associates with producers. His thoughtful disposition prompted him to push his collaborators to take their work seriously. He knew the value of a pound, and saw to it that the films he produced were executed with a glossy veneer which hid their humble origins. It was an attitude that he did his best to implement on every picture he ever produced.

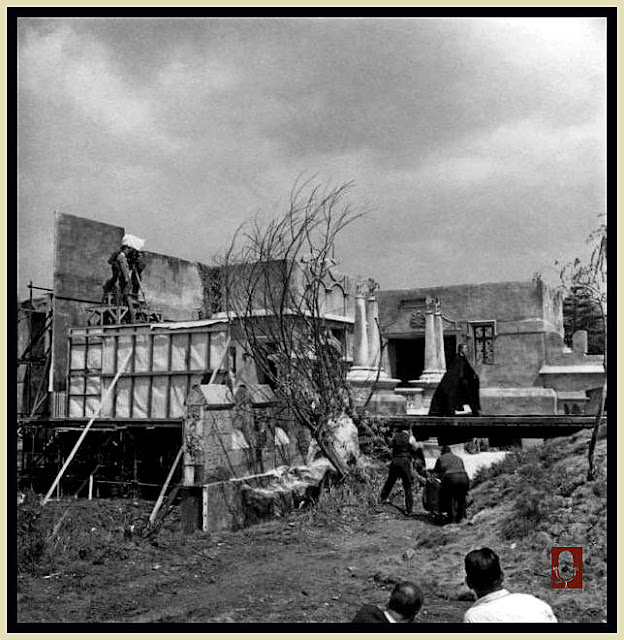

In time, Hinds branched out yet again, this time becoming a screenwriter. The

story goes that Hammer’s planned historical epic, The Rape of Sabena,

fell afoul of the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC), thus leaving

Hinds in a bit of a predicament. He had already authorized

Bernard Robinson to build some imposing “Spanish” sets, and now that

this particular property was dead in the water, he had to find a way to

utilize these sets. Hinds turned his attention to Guy

Endore’s novel The Werewolf of Paris – realizing that Hammer had yet to

make their own werewolf film, he decided to change the setting from

Paris to Spain, thus enabling the studio to make use of these

troublesome sets. Looking to save a

buck, Hinds elected to write the script himself – and he found that he

preferred the process of creating scenarios to dealing with the

bureaucratic nightmares associated with producing. Hinds

would continue to produce throughout the better part of the 1960s, but

when he found himself working “under” American producer Joan Harrison on

Hammer’s ill-fated venture into anthology television, Journey into the

Unknown, he decided to call it a day. Hinds would later

recall working with Harrison (or as often was the case, being at

loggerheads with her) on this problematic production to be a dispiriting

affair which he was in no great hurry to relive. And thus

it came to be that producer/writer Anthony Hinds became “plain old”

writer Anthony Hinds… or John Elder, as the self-effacing scribe decided

that having his

name plastered all over the credits might look a bit conceited. As

a writer, Hinds’ credits include Kiss of the Vampire (1962), Phantom of

the Opera (1962), The Reptile (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman

(1966), Taste the Blood of Dracula (1969), and Frankenstein and the

Monster from Hell (1972). He eventually left Hammer for a time, going to work for rival company Tyburn Productions. For them, he scripted The Ghoul and Legend of the Werewolf in 1974. His

final credits would include an episode of Hammer House of Horror,

titled Visitor from the Grave, and a “story by” credit on Tyburn’s made

for TV Sherlock Holmes adventure, The Masks of Death (1984), starring

Peter Cushing and John Mills.

Hinds went into retirement in the 80s, granting the occasional interview, but basically content to enjoy his “golden years” on his own terms. A quiet, humble and unpretentious individual, he reacted with genuine surprise (and pride) when his many classic Hammer productions were dredged up and celebrated as classics of their kind. True to form, Hinds never seemed to take himself too seriously – but his passion for the work itself was obvious. With his passing on September 30th (a mere 11 days after his birthday), the key architect of Hammer horror passed to the great beyond. Indeed, of the key creative personnel who created this world that we fans know and revere so much, only one remains standing: Christopher Lee, himself a mere four months Hinds’ senior. Hinds’ passing may not signal the end of an era, but it does put one in a reflective mood as we look back and celebrate the many wonderful achievements of one of the British film industry’s unsung treasures.

Troy Howarth

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf

Hammer Film fans across the globe were saddened yesterday by the news that Anthony Hinds had passed away at the grand age of 91. Hinds is seldom discussed as much as Peter Cushing. Or Christopher Lee. Or Terence Fisher. Or Jimmy Sangster. Or Jack Asher. Or

Bernard Robinson. But the fact remains, it was Hinds who assembled

these gifted men, thus creating “Hammer Horror.” - See more at:

http://petercushingblog.blogspot.co.uk/#sthash.ApafMCzc.dpuf